My wife subscribes to The New Yorker magazine, which means I

can also read every issue on my first-gen Kindle Fire using the Amazon App

Store’s New Yorker app.

Since receiving my Kindle Fire in November 2011 I’ve

downloaded perhaps a dozen New Yorker issues

and, despite the time and design savvy that obviously went into the app, by now

I’d largely lost interest in reading the magazine this way. Aside from the long download times each 75MB

to 150MB issue requires (even with decent cable modem speeds it takes several minutes

before one is ready to read), I found the added features—sound clips, slide

shows, the occasional video—underwhelmng.

The printed word has always been what The New Yorker is all about. The app, not surprisingly, didn’t seem to change that.

Until the other day.

Browsing the print edition issue for Feb. 11 & 18, 2013, I came across what I quickly decided was an all-too-cute profile of an artist

whose strenuously whimsical paintings depicted one thing and one thing only:

the grocery aisles at WalMart. That article

had been titled, predictably, “WALART”.

The first page looked like this:

With nothing better to do I read the piece, which wasn’t

lengthy, and didn’t find much to change my mind about the artist, Brendan O’Connell. He struck me as a lucky stiff who’d stumbled

upon a formula for selling gimmicky, otherwise forgettable pictures about an (ironically)

iconic American institution. That he

based his paintings on photographs he took himself—photographs that until

recently got him thrown out of WalMart, which doesn’t allow picture-taking on

its premises (but has now made an exception for O’Connell, because he’s become

something of a celebrity)—didn’t change my opinion of him or his work.

Until a day or two later, when I downloaded the Feb 11 & 18, 2013 issue to my Kindle

Fire.

If you take another look at the first page of the story

(shown above) in the New Yorker’s

print issue, you’ll see a picture of O’Connell in his Connecticut studio

sitting in front of some of his works.

Now, as it happens, in the print edition that photograph is your sole means

of evaluating O’Connell’s art. There are

no other examples of his paintings attached to the piece by Susan

Orlean, which runs a mere 5 pages.

In the New Yorker

app issue, however, you’re given a slide show of 7 of O’Connell’s paintings. And when I viewed them (some I was already familiar

with because Orlean had described them in her article), even on my Kindle Fire’s modest 7-inch screen I could scarcely believe

they were done by the same guy gloating in front of those seemingly slapdash drippy Warhol-derivative riots of color you can barely make out in the print article’s one photograph.

Here’s the slideshow:

|

| Note: The New Yorker app appears unable to render slide shows like these in landscape mode. |

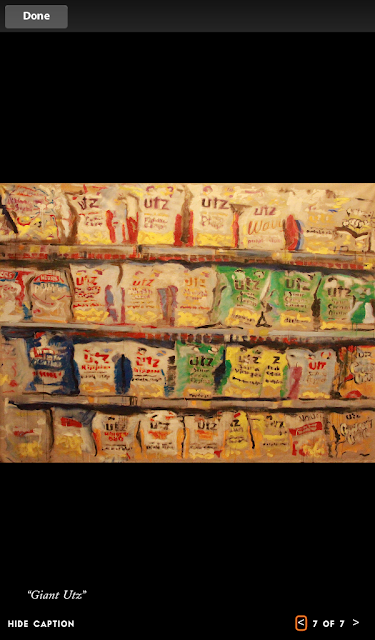

Seeing even these tiny reproductions was shocking. There was no question that “Catskills” was deft and playful and amusing. I’m not sure I like the idea behind “Whistlers Mother”, since the name stems only from the profile of the woman on her Jazzy and its passing resemblance to Whistler’s portrait in profile of his mother; there’s also a Diane Arbus quality to the picture that detracts from its mirth. “Wonder Bread”, on the other hand, is nearly (and improbably) photorealistic, done with just enough carelessness to magically suggest brushstrokes. I’m not sure how I feel about “Foraging (I Want Candy)”; the girl’s tendrils of hair remind me somehow of Edvard Munch, which put it at odds with its bright colors and childhood subject. I don’t feel qualified to comment on “Checkout” because the image (and perhaps the original?) is so damned tiny. (Update: actually, “Checkout” turns out to be a rather enormous 7 feet by 8 feet.) But “Elmers” is quietly joyous for anyone who’s ever made art in grade school, and “Giant Utz” manages to depart magnificently from the near photorealism of “Wonder Bread”. It defiantly pulls apart the integrity of the Utz snack bags and their designs and very nearly, but not quite, discards them for an abstract study in chaotic yellow, orange, and green rectangles that slightly resemble shooting gallery targets. It is genuinely whimsical and just plain fun. As are most of these works.

So while I may not have fallen in love with everything in the slideshow, is there any question I was humbled by this experience and

more than a little troubled by it? How

could I have read this article on Brendan O’Connell via two different delivery

platforms that brought me to two such entirely different conclusions about the man and his art?

There’s a message here for those trying to reinvent

magazines or illustrated books or any medium that relies on conveying images

well. It begins with the vexing reality

that image-intensive files tend to be enormous (this New Yorker app edition weighed in at about 153 MB) and time-consuming to download, making them

unwieldy and unattractive, and ends with the invigorating if obvious conclusion

that if you want to write about an artist you’d better show professionally

scanned samples that bring his or her work to life.

Inviting readers to appraise an artist’s work and not just hear a good story about it—to take them by the lapels and insist they look at some pieces—enjoins them to pay attention and take an active role. I know we’re not accustomed to thinking of reading as passive, but in this case, for me, it was.

Inviting readers to appraise an artist’s work and not just hear a good story about it—to take them by the lapels and insist they look at some pieces—enjoins them to pay attention and take an active role. I know we’re not accustomed to thinking of reading as passive, but in this case, for me, it was.

I jumped to conclusions, Mr. O’Connell. For that I apologize.

Postscript: Brendan O’Connell appeared as a guest on The Colbert Report on March 6, 2013. His “Giant Utz”—which O’Connell refers to on the show as “Great Big Utz”—was one of the pictures Colbert displayed during the interview. I was surprised to hear O’Connell refer to “Great Big Utz” as a very large painting (“like 7 feet by 8 feet”) with, after some prodding by Stephen Colbert, a very large price to match: $40,000. So as limited as The New Yorker magazine’s profile of O’Connell may be, I guess The New Yorker app’s slide show on my 7-inch Kindle Fire had its own limitations.

For a slightly different take on what can happen when words and graphics are embedded together in a file, see the difficulties I encountered reading the so-called Powerpoint chapter of Jennifer Egan’s novel A Visit From the Goon Squad on my android phone and first-gen Nook.

Postscript: Brendan O’Connell appeared as a guest on The Colbert Report on March 6, 2013. His “Giant Utz”—which O’Connell refers to on the show as “Great Big Utz”—was one of the pictures Colbert displayed during the interview. I was surprised to hear O’Connell refer to “Great Big Utz” as a very large painting (“like 7 feet by 8 feet”) with, after some prodding by Stephen Colbert, a very large price to match: $40,000. So as limited as The New Yorker magazine’s profile of O’Connell may be, I guess The New Yorker app’s slide show on my 7-inch Kindle Fire had its own limitations.

* * *

For a slightly different take on what can happen when words and graphics are embedded together in a file, see the difficulties I encountered reading the so-called Powerpoint chapter of Jennifer Egan’s novel A Visit From the Goon Squad on my android phone and first-gen Nook.

No comments:

Post a Comment